When it comes to creating a balanced training program, I definitely prefer to write and recommend training that emphasizes the posterior chain. Let’s consider the posterior chain as everything on the back of your body, from the back of your head to your heels. Typically, the range of this emphasis is anywhere from a two-to-one ratio of pulling to pushing, all the way up to a four-to-one ratio. How is that balanced, you ask? It’s balanced based on life and your daily activities.

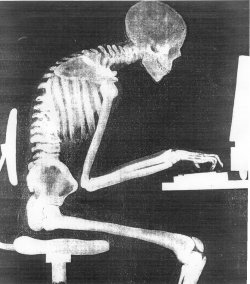

Regardless of what type of device you’re reading this on, I’m willing to get you’re sitting down and slouched over. If your hands are on a keyboard, you’re probably internally rotated and I bet your shoulders are shrugged as well. That kyphosis, scapular elevation, humeral internal rotation, and cervical hyperextension aren’t sexy. Basically, you look like this dude:

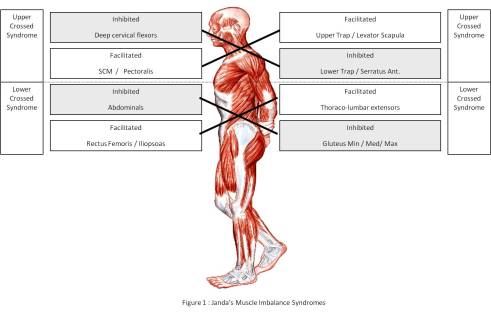

Writing and recommending programs that have an imbalance towards the posterior chain helps to combat some of the imbalance of our daily lives; most people are constantly stuck in some sort of seated or hunched position, which causes adaptive shortening throughout the body, including at the calves, hip flexors, pecs, lats, and biceps. While those muscles become accustomed to a shortened position, their antagonists get used to a lengthened resting position. Our habitual postures lead to chronic facilitation or inhibition of muscles, resulting in what Janda called the Upper and Lower Crossed Syndromes:

To make maters worse, the folks that do exercise tend to have a fascination with their calves, quads, pecs, and biceps, and choose exercises that exacerbate their already poor posture. We’re a society that loves bench presses, bicep curls, and those stupid leg press machines. Instead, we should be focusing on exercises that recruit the muscles we can’t see in the mirror as much as possible.

Based on this idea, pulling exercises become much more important than pushing exercises. If I compare the ‘big’ lifts as pushing and pulling exercises, we’d have this chart:

|

Pulling |

Pushing |

| Deadlift | Squat |

| Inverted Row | Bench Press |

| Chin-Up | Military Press |

For each of those exercise pairings, compare the balance of both your maximal strength numbers (1RM, 3RM) to your repetition effort numbers, and your overall training volume. If you’re outperforming your pushing to your pulling, you may want to consider exactly how you’re sequencing your training, and make some changes to help bring some balance into your program, and hopefully keep yourself pain and injury free.

With the deadlift and squat, there are several factors that come in to play, and you’re likely thinking “I definitely squat more than I deadlift.” Nay, I say, or you squat high. If you claim to squat in the 500’s but only deadlift mid 300’s, you may want to figure out what it feels like to squat to a box, and one that’s actually to parallel. I’ll use those little aerobics risers at my gym, and will fluctuate between 2 risers and a step for front squats and 4 risers and a step for sumo stance squats. The box keeps my depth honest, and provides me some feedback so I can accurately compare pushing (squat) to pulling (deadlift) strength. Unlike squatting and deadlifting with proper form, which is a great idea, I don’t think leg pressing is ever a good idea. It contributes to muscle imbalances, let’s you pack on extra weight and increases your risk of injury.

A few weeks ago Ben Bruno published a great post about comparing endurance strength with the push-up and the inverted row. The test was conceived to assess upper back strength/endurance, and I think it’s definitely something that should be done to get a baseline for where you have weaknesses. Most people, myself included, can bang out more push-ups than they can rows, but enhancing upper back strength and endurance will be in your best interest, both for adjusting pushing/pulling strength ratios, but also for improving posture and reducing injury risk. The link to Ben’s article is HERE, but his rules are simple:

Do a set of inverted rows with your feet elevated on a standard weight bench. The straps or bar (I prefer straps, but I understand not everyone has access to them) should be set at a level that when your arms are fully extended, your upper back is approximately two inches off the ground. If you’re using a bar, perform each rep so that your chest touches the bar and your arms fully extend at the bottom. If you’re using straps, your hands must touch your chest on every rep.

I’m less willing to tell you to go perform some chin-up and military press testing, as most people’s form makes them look like a mannequin being controlled by a 3 year old. If you can complete your chin-up reps from a dead hang, and you can military press out of the rack without turning it into a lay-back press, then you should be okay to compare them. I prefer 3 rep max numbers for these two lifts, and the chin-up should be completed as a sternum up: Chest to bar, none of this pelican-neck crap that people try to get away with.

If you get a chance to test and compare these numbers, or you review your overall training lay out by reviewing program notes, you’ll be presently surprised to see that you do a lot more pushing than pulling. Change that.

Add more pulling volume, say with inverted rows, face-pulls, and pulls ups for the upper body, and deadlifts, pull-throughs, and hip thrusts for the lower body. The posterior chain is more important for athletic performance, and probably for physique as well. Seriously, doesn’t everyone love a good set of glutes and strong rhomboids?

Leave a comment